A Thematic Study of the Book of Hebrews, Part 5

Understanding Hebrews Chapter 6

Introduction

In the previous article, I analyzed Hebrews 5 by outlining it and determining its thematic structure. In that analysis I determined that Hebrews 5 consisted of two thematic sections. Hebrews 5:1-10 was one thematic unit and Hebrews 5:11–6:3 was a second. Furthermore, I discovered that Hebrews 5:1-10 was written chiastically, and Hebrews 5:11–6:3 was written as a synonymous parallelism. Therefore, since the first three verses of Hebrews 6 are thematically connected to the material from chapter 5, I will begin my study of Hebrews 6 at verse 4.

An Outline of Hebrews 6

Hebrews 6 Outline Analysis

As you can see, I’ve divided Hebrews 6:4-20 into two major sections. When I outlined this chapter I noticed how vv. 4-8 consisted of a very stark warning, whereas vv. 9-20 consisted of an encouragement to endure. Taken together, this section is known in theological circles as a hortatory passage. The word hortatory is an adjective that means encouraging or exhorting—especially in a manner that compels someone to take action, and it often describes speech or writing that is meant to inspire or persuade. As you read through the book of Hebrews, it’s impossible to miss these hortatory sections. Here are a few for you to consider:

Therefore we must give the more earnest heed to the things we have heard, lest we drift away. 2 For if the word spoken through angels proved steadfast, and every transgression and disobedience received a just reward, 3 how shall we escape if we neglect so great a salvation, which at the first began to be spoken by the Lord, and was confirmed to us by those who heard Him (Hebrews 2:1-3)

Beware, brethren, lest there be in any of you an evil heart of unbelief in departing from the living God; 13 but exhort one another daily, while it is called “Today,” lest any of you be hardened through the deceitfulness of sin. 14 For we have become partakers of Christ if we hold the beginning of our confidence steadfast to the end (Hebrews 3:12-14)

Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for He who promised is faithful. 24 And let us consider one another in order to stir up love and good works, 25 not forsaking the assembling of ourselves together, as is the manner of some, but exhorting one another, and so much the more as you see the Day approaching. 6 For if we sin willfully after we have received the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, 27 but a certain fearful expectation of judgment, and fiery indignation which will devour the adversaries. 28 Anyone who has rejected Moses’ law dies without mercy on the testimony of two or three witnesses. 29 Of how much worse punishment, do you suppose, will he be thought worthy who has trampled the Son of God underfoot, counted the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified a common thing, and insulted the Spirit of grace? (Hebrews 10:23-29)

As you can see, the book of Hebrews has a number of hortatory sections as prominent features of the book. As you continue to read and study Hebrews, you should take special notice of these portions. They will become extremely important as we try to determine the overall purpose of the book.

Chiastic Analysis of Hebrews 6

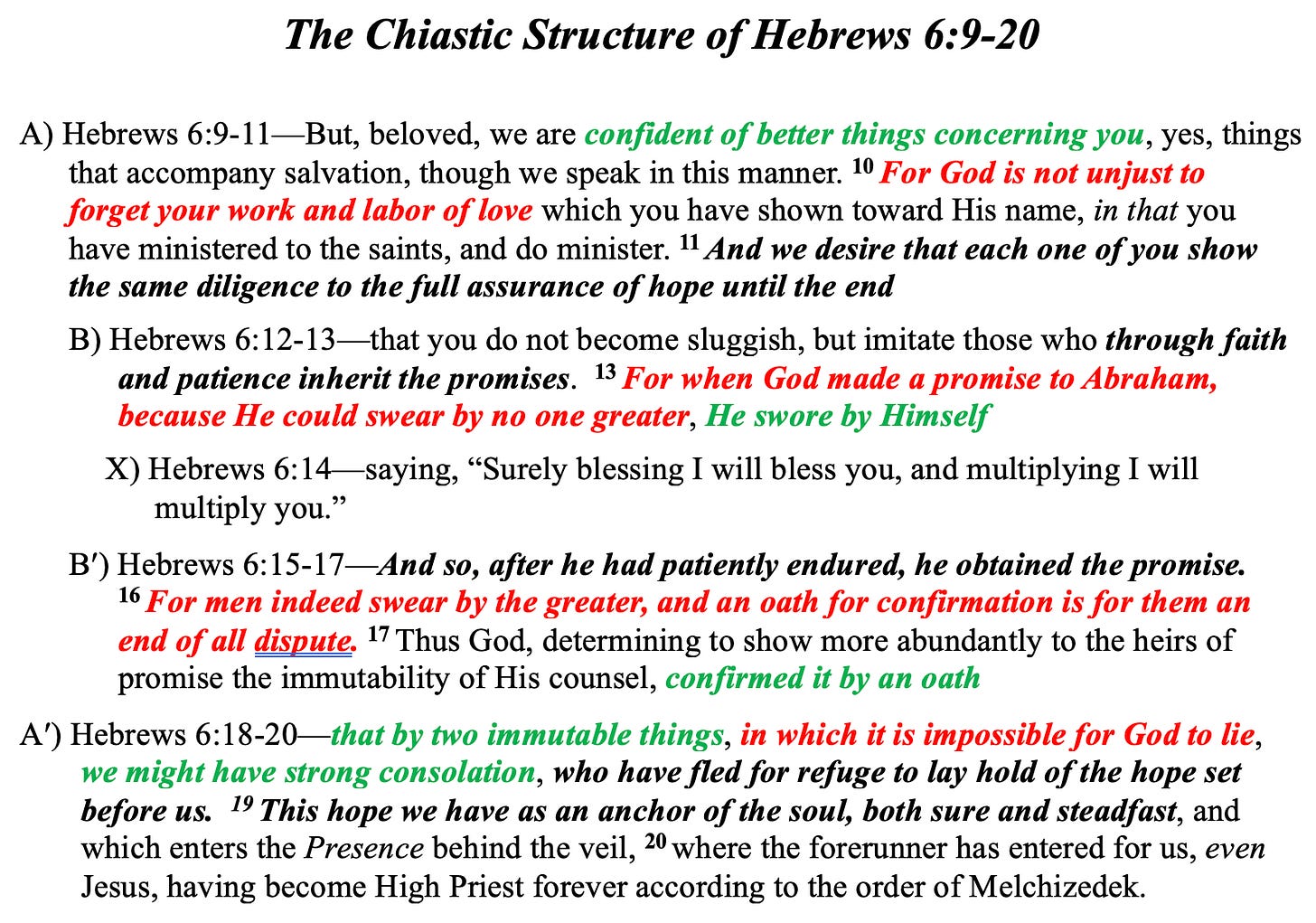

Closer thematic examination of my outline of Hebrews 6 revealed that its two thematic units (A and B) were also the boundaries for the beginning and ending of two thematic structures. It just so happens that Hebrews 6:4-8 consists of a parallelism, and Hebrews 6:9-20 consists of a chiastic structure. As a quick review, remember that chiastic structures and parallelisms are simply thematic presentations of a story, where themes in the first half of the story are repeated in the second half. In a parallelism, the themes in the first half of the story are repeated in the second half in the same order as follows:

In a chiastic structure, the themes in the first half of the story are repeated in the second half in reverse order as follows:

During your own reading you may find that chiastic structures are referred to by another name—an inverted parallelism. So don’t get confused by the terms. Basically, Biblical scholars are using terms to recognize parallelism, or the repetitious nature of Scripture. When scholars see things of this nature they try to give names to them, but quite often, everyone does not abide by the same nomenclature, so a little confusion may be the result. Basically, whether we’re talking about a parallelism or a chiastic structure as I’ve drawn them above, they both involve repetition of similar themes. The difference is in how the themes are repeated. If they are repeated in the same order, as in the first diagram above, then technically it is called a synonymous parallelism. If the themes are repeated in reverse order, as in the second diagram above, then technically it is called an introverted or inverted parallelism. Furthermore, introverted/inverted parallelisms are sometimes called chiastic structures or chiasms. So, for the record, I typically refer to a synonymous parallelism simply as a parallelism, and I refer to an introverted/inverted parallelism as a chiastic structure.

Chiastic structures are analyzed by comparing and contrasting the similar themes on the opposite sides of the structure—compare A to A’ and B to B’, etc. By themes, I mean similar words, phrases, situations, circumstances and events. Sometimes the connections between the two halves of a thematic structures are easy to identify and sometimes it takes more “work.” This parallelism is easy to understand, but maybe not so easy to discover, primarily because the themes in the first and second halves are not literally the same. Theme A in the first half mentions people who have “tasted” (two times), and “become partakers of,” both acts of consumption. These are matched in the second half, A’, by the similar theme of consumption in the words “drinks,” “comes upon it,” and “receives blessing from God.” The matching theme being that in both instances consumption is occurring. In A, people are consuming the goodness of things from Adonai. In A’, the earth is consuming the rain and blessing from Adonai. So, as you can see, the connections are sure and objective.

Looking to B and B’, the connection may be harder to see, but let’s give it a try. In B, we see a negative consequence upon those who have consumed the good things from Adonai, yet have not grown and produced fruit. This is thematically connected to B’, where we see a negative consequence for the land which has consumed water but has not grown and produced fruit. The parallel/analogy is obvious. People who sit and consume the word of God and experience Adonai’s supernatural goodness without bearing fruit and experiencing growth are like land that takes in rain, yet never produces a bountiful harvest. As I’ve stated before, the beauty of following the thematic progression of Scripture is that we are “getting inside the head” of the author—a behind-the-scenes view of the who, what, when, where, why and how of his thoughts! We are learning about and understanding his logical flow of thoughts and tracking along with him as he develops his case. What’s more important though, is that we realize what Peter said: “knowing this first, that no prophecy of Scripture is of any private interpretation, 21 for prophecy never came by the will of man, but holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1:20-21). In other words, when we understand the thoughts, musings and deliberations of the author of Scripture, we are understanding the thoughts, musings and deliberations of the One who inspired the words. And I like that idea!

As I’m performing my trek through the book of Hebrews, I’m also studying what commentators and scholars have said about the book. It’s fascinating to read what the leading scholars on the book of Hebrews have to say. And, although I may not agree with some of the things they have to say, I learn quite a bit from their diligent work. I also use their work as a source of checks and balances for the work I do. In other words, it’s important to me that my thematic analysis can be corroborated by others. One area of research that concerns scholars pertains to the structure of a Biblical book. They spend hours delving into the clues that help them understand how a book is arranged and/or organized. Understanding the organization of a Biblical book is very important because understanding its organization will help with its interpretation. So, I’m always interested in seeing if my organization and divisions of a book are corroborated by the scholars. When we track along perfectly, I see that as a positive. Sometimes there are differences in how I organize a book compared to the commentators. When this happens, I try to reconcile the two. Sometimes, in the end, their analysis is more complete, and I take that into account and modify my analysis. At other times, I simply disagree with their analysis and keep mine, cognizant though, of the reasons why I prefer my analysis.

Considering Hebrews 6:4-8, scholars have noted the unity of this small passage. It is amazing because they don’t all use the same type of analyses. So, it’s very interesting to see different approaches to a passage that yield the same or similar results. For example, G. H. Guthrie, a leading scholar on the book of Hebrews, chose Hebrews 6:4-8 as the hortatory central axis for an overall book-level chiastic structure for the book of Hebrews.[1] I don’t agree with its placement at the chiastic center of the book of Hebrews, but I mention it because he has noted its prominence as a complete thematic unit. Both Neeley and Lane connect Hebrews 6:4-8 with Hebrews 10:26-31 in their overall thematic structure for the entire book of Hebrews, again, showing that others have noted its thematic unity.[2] Next, let’s analyze the chiastic structure of Hebrews 6:9-20.

Element A/A’

Elements A/A’ are beautifully connected by three separate themes. First of all, in element A’, the author states that there are two immutable things that bring strong consolation to his hearers—Adonai’s promise and His oath. Both of these two immutable things are the basis for consolation to those who have fled for refuge. The very definition of consolation pertains to those who have received comfort in their distress. The author’s readers had suffered persecution—their present distress. And he was offering them comfort—encouragement concerning Adonai’s faithfulness, arising from His promise and oath, the two immutable things. Typically, when someone is consoled (comforted in distress), it will lead to a greater sense of confidence for the future. And this is how element A’ is beautifully thematically connected to element A in the first half! Element A in the first half uses the word confident. In other words, the pastor is expressing his confidence for his readers because he knows they will be comforted in their distress even as he was. Notice how he includes himself when he states, “that by two immutable things, in which it is impossible for God to lie, we might have strong consolation.” Thus, we know that he had confidence because of Adonai’s faithfulness, and he was anticipating the same confidence in his readers. Thus, it is very easy to see how the themes of confidence and consolation found in the two halves work together. The picture painted is thus. The author’s confidence in his readers (Hebrews 6:9) is thoroughly grounded in their collective consolation, which is provided by Adonai’s promise and oath (Hebrews 6:18). This beautiful picture is seen when you notice the chiastic presentation of these two themes and connect them properly. This is another perfect example of how the authors of Scripture often present a theme early on, only to return to it later. Knowing this and recognizing this helps us to be better interpreters of the word.

The second theme pertains to Adonai’s faithfulness. This is captured for us in the first half, A, when it states, “For God is not unjust to forget your work and labor of love” (Hebrews 6:10). A similar theme is revisited in the following phrase, “in which it is impossible for God to lie” (Hebrews 6:18) in A’. The phrase in theme A pertains to Adonai’s justice, whereas the theme in A’ concerns His truthfulness. Thus, we can be confident that He will not forget our works of love, neither will He break His promises. Taken together, these two themes which emphasize the grandeur of Adonai’s divine attributes, are meant to provide comfort to the Hebrews.

The third theme connecting A to A’ highlights the hope the Hebrews have because of Adonai. In A the author encourages his readers to show diligence until the end. And what are they to show diligence to? The full assurance of hope. In other words, the author is expecting his readers to have full assurance of hope, and he is expecting them to show unwavering diligence to that hope. This is thematically connected to A’, where he notes that this hope is an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast. Taken together, these two passages teach us that we are to exercise diligence until the end, specifically because our hope is so steadfast and secure.

Element B/B’

As I’ve mentioned before, the connecting themes in a chiastic structure (or a parallelism) typically exist on a continuum as far as ease of identification is concerned. Some connections are extremely easy to see, some are intermediate in complexity, and others are sometimes difficult. Nonetheless, the connections should be objective and therefore easy to see and understand once expounded upon. The connecting themes in element B/B’ are very easy to see and understand, much easier than those I’ve discussed in elements A/A’. In element B, the author encourages his readers to imitate those who “through faith and patience inherit the promises.” This is thematically connected to B’, where he presents Abraham as one who after he “had patiently endured, he obtained the promise.” Secondly, elements B/B’ both focus on the idea of swearing by someone greater. Lastly, element B mentions that Adonai “swore by Himself.” This is thematically connected to element B’, where it states that Adonai confirmed his promise with an oath. In both instances, Adonai was doing diligence to ensure that what He had promised was sure to occur.

Lastly, the central axis pertains to the promise Adonai gave to Abraham, thus focusing on the fact that Abraham was pursuing a promise that Adonai had made to him. And, as you can easily see, this example dovetails with the primary consolation being offered by the author—the idea that although Adonai makes promises, it’s up to us to endure until we see the fulfillment of the promise.

In my next article, we will continue looking at how the author of Hebrews developed his thoughts. It is very apparent that the entire book of Hebrews will most likely consist of one thematic unit followed by another. Our blessing will be to put it all together once we’ve garnered all the pieces!

[1] George H. Guthrie, The Structure of Hebrews: A Text-Linguistic Analysis (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1994), 136, 144.

[2] Linda Lloyd Neeley, “A Discourse Analysis of Hebrews,” Occasional Papers in Translation and Textlinguistics 3-4 (1987): 1-146; William L. Lane, Hebrews. 2 vols. Word Bible Commentary 47a and 47b. Edited by David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker. Dallas: Word, 1991.